Final Project, Muhammad Ahmed, Word Count: 1751

Slavery in Union County

In the shadow of the American Civil War, this article delves into the nuanced tapestry of Union County’s historical struggle with slavery. It begins with the haunting presence of slavery before the Revolution and details the slow yet significant steps towards abolition, set against a backdrop of national turmoil.

Richard A. Sauers in his book “Union County, Pennsylvania, and the Civil War” explores the history and effects of slavery within the context of Union County, detailing the gradual decline of slavery and the rise of abolitionism in the area, set against the broader national conflicts leading up to the Civil War. Sauers starts by noting the early presence of slavery in Union County, indicating that, “Slaves were present in what-is-now Union County well before the American Revolution,” as documented by John B. Linn in his “Annals of Buffalo Valley.”

Pennsylvania’s legislative actions against slavery began with the 1776 constitution that allowed free black males various civil liberties and the gradual abolition law of 1780, which intended to phase out slavery. However, Sauers points out a loophole that initially allowed the continuation of slavery: “On the surface this law seemed revolutionary in an age of discrimination, but in reality the loopholes allowed slave owners to hold in servitude the children of these ‘term slaves’ for 28 years.” It wasn’t until 1826 that the state Supreme Court rectified this, limiting the servitude to only the first generation born before the law.

The national Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, which allowed slave owners to recapture escaped slaves, affected Pennsylvania significantly, leading to the 1820 “Act to Protect Free Negroes and to Prevent Kidnapping,” Sauers highlights. He also discusses the political turmoil of the 1830s that saw the rise of abolitionist movements and the controversial revocation of voting rights from free black men in Pennsylvania in 1838.

Despite the growing abolitionist sentiment, Union County was relatively quiet on the matter until the 1840s. Sauers notes the decrease in slaves and increase in free blacks living with white families, demonstrating a shift in social dynamics. Yet, he also mentions the lack of detailed records on the lives of African Americans, stating, “The lives of African Americans, whether they were slaves or free, is largely undocumented.”

The role of newspapers in disseminating information about African Americans and slavery is also discussed. Sauers points out that early newspapers like “The Union Times” occasionally mentioned African Americans, such as in the 1826 advertisement for the sale of a young black boy or the marriage of Jacob Boyer and Rebecca Collier in the “People’s Advocate.”

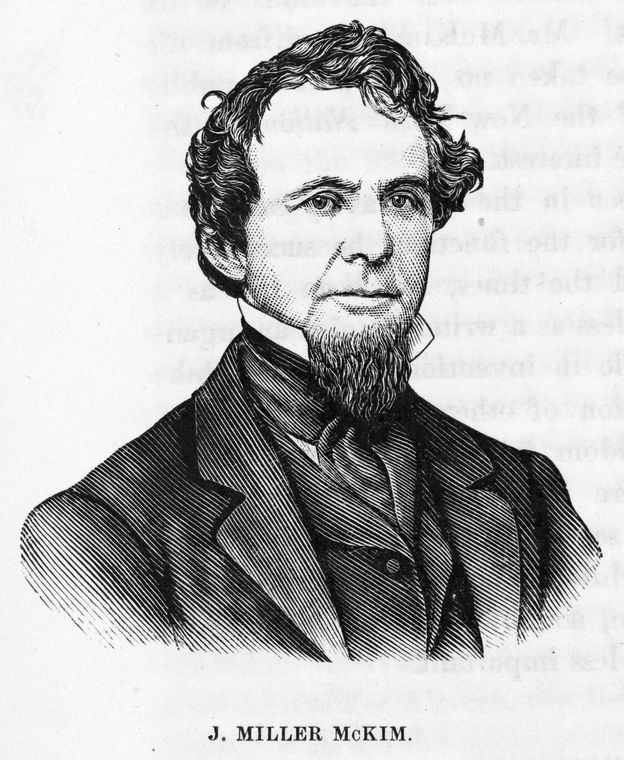

Sauers elaborates on the complex attitudes towards abolitionism in the county. Despite the initial silence, the arrival of abolitionist James Miller McKim in 1837 marked a significant moment. McKim’s efforts, however, met with mixed responses, illustrating the divided opinions on slavery. Sauers recounts, “Miller McKim delivered his first lecture in Lewisburg on the abolition of slavery…ending suddenly in a small riot,” indicating the contentious nature of the issue.

As the country moved towards the Civil War, Union County, like many parts of the North, gradually aligned with the abolitionist cause, influenced by national events and the strong voices of local and visiting abolitionists. This alignment was reflected in the changing content of local newspapers and public meetings, which increasingly supported the anti-slavery movement.

Bruce Teeple in his Interview and article sheds light on the complex history of slavery and abolition in Pennsylvania. Despite passing the first abolition law in 1780, Pennsylvania’s journey towards true emancipation was fraught with loopholes and legislative oversights that allowed slavery to persist under different guises.

Teeple points out, “Article of Agreement… illustrates the reality of the ‘peculiar institution’s’ presence in our own backyard,” highlighting a transaction in 1824 where a woman named Alice was sold for $50. This sale, occurring decades after abolition, raises significant questions about the effectiveness of the law and the ongoing practice of slavery in the state.

Teeple emphasizes the limited impact of the 1780 abolition law, stating, “While Pennsylvania trumpeted its abolition law as the nation’s first, the step was small and overrated.” He notes that many slave owners circumvented the law by selling their slaves out of state, ensuring continued profits.

Furthermore, Teeple reveals the systemic discrimination that persisted even after formal abolition, noting that “in spite of growing abolition sentiment nationwide, Pennsylvania’s court decisions in the 1830s reflected widespread social discrimination.” The state’s reluctance to fully embrace abolition reflected broader societal attitudes that continued to marginalize African Americans.

In addition, the article discusses the 1788 amendment to the original abolition act, which aimed to close loopholes that allowed slave owners to exploit their slaves further. This amendment included provisions to prevent the separation of slave families and to restrict the movement of pregnant slave mothers across state lines.

Jeannette Lasansky’s work, “Slaves and Free African Americans in the Buffalo Valley 1780-1850,” reveals the existence and complexities of slavery and freedom for African Americans in Pennsylvania, an area often overshadowed by more notorious slaveholding regions. Lasansky opens with the surprising fact that, “Slavery existed in Pennsylvania… in 1790 the ratio was nearly one slave out of every 100 people.” Despite its lower prevalence compared to states like Virginia, the institution was equally harsh, involving the selling of humans, often breaking families apart.

Historically, she notes, “Slavery was an old institution often associated with the spoils of war, but slavery took a different form in the western hemisphere.” This included a lucrative slave trade through the Caribbean, dominated by traders such as the Brown family of Rhode Island. Despite Pennsylvania’s introduction of a gradual abolition law in 1780, true freedom for African Americans was delayed by subsequent legislation and persistent racial discrimination.

Lasansky points to Pennsylvania’s separate court system for blacks initiated in 1725 as an early form of institutionalized discrimination, which persisted even as Quakers like John Woolman and Anthony Benezet advocated for abolition. She describes how, “Quakers… preached against owning slaves, saying ‘do unto others as you would have done unto you.’” Yet, it wasn’t until the 1830s that abolitionist movements gained significant traction with the establishment of vigilance committees to aid runaway slaves.

Tax records from the era show the gradual decline of slavery in the region, with figures like James Dale listed as one of the last known slaveholders in Union County by 1840. The publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in 1852 and the Civil War further catalyzed the abolitionist movement, yet, as Lasansky recounts, “the last slaves were still within [John Blair Linn’s] memory” when he published his “Annals of Buffalo Valley” in 1877, indicating the slow progress toward true abolition.

“Copperheads” (Southern supporters)

In the 1860s, the Copperheads, also known as Peace Democrats, emerged as a controversial faction within the Democratic Party. They opposed the Civil War and advocated for an immediate peace settlement with the Confederates. According to historians, “Copperheadism was a highly contentious grassroots movement” with a strong base in the Midwest and urban ethnic wards. They viewed themselves as defenders of traditional values and constitutional rights, which they believed were being undermined by the Republican Party’s war policies.

Jim Pangburn, reflecting on the reach of the Copperheads, noted their secretive nature and limited activity in some regions: “There was the organization called the Knights of the Golden Circle which was sympathetic to the Confederates,” he said. “They were selling hand signals that would identify them as being sympathetic to the Confederacy, but they were not active much around here,” referring to their presence in Pennsylvania.

The term “Copperhead” itself has a venomous origin, taken from the eastern copperhead snake, symbolizing both danger and stealth. The Copperheads adopted this symbol with a sense of pride, reinterpreting it as a badge of liberty. They were starkly opposed to the war, not out of sympathy for the Southern cause, but from a fierce desire to return to peace and normalcy. Their motto, encapsulated by leader Clement Vallandigham, was to “maintain the Constitution as it is, and to restore the Union as it was.”

Copperheads were vocal in their opposition to President Abraham Lincoln, whom they saw as a tyrant trampling on civil liberties. “They talked of helping Confederate prisoners of war seize their camps and escape,” showcasing their willingness to act against the Union war efforts. This group was infamously known for their resistance to the draft and for encouraging desertion among Union troops. Their activities prompted Republican accusations of treason, particularly in a series of trials in 1864.

Their influence in politics was significant yet fluctuated with the fortunes of war. “Copperhead support increased when Union armies did poorly and decreased when they won great victories,” a pattern that held until the Union’s successes in 1864, such as the fall of Atlanta, which led to the movement’s rapid decline. Their opposition to the war made them targets for Republican campaigns, particularly during the 1864 presidential election where they were used to discredit Democratic candidates.

The Copperheads’ impact on the Northern home front was profound. They held numerous newspapers that criticized Lincoln and his policies with vehement rhetoric. One notable editor, Marcus M. Pomeroy of the La Crosse Democrat, harshly described Lincoln as a “worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero.”

Harry D. Lewis, discussing Copperhead characteristics, highlighted their distinctive appearance and tactics: “They wore baggy clothes, French fashion, recruited from firehouses from Philadelphia,” he said. “Deployed tactics that were different from conventional Union soldiers,” illustrating their attempt to stand apart even in their visual representation. Lewis also remarked on the changing sentiments during the war: “At the beginning of the Civil War about 1% supported abolition, but gradually people changed,” indicating a shift in public opinion that ultimately undermined the Copperhead stance.

Despite their fervent activities, the Copperheads’ plans for more organized resistance never fully materialized. They were often under surveillance, and their leaders, like Vallandigham, faced arrest and military trials. This repression culminated in the Supreme Court case Ex parte Milligan, which ruled that civilian trials must be used where available, striking a blow to military tribunals for civilians.

Ultimately, the legacy of the Copperheads is a complex one. Historians debate their actual threat to the Union war effort and the extent to which their civil liberties were unjustly violated.

Note: I wasn’t able to find much information about the Local Civil War reenactments, as most people said they don’t know, and there weren’t many reenactments around here, as stated by the people I interviewed.

Interviews:

I conducted three interviews with Bruce Teeple, Harry D. Lewis, and Jim Pangburn (on Zoom). Bruce Teeple and Harry’s interview is recorded together, so I’m posting it as one.

Link for Bruce Teeple and Harry D. Lewis:

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MofjqhFYHks

Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjNtig1QN-E

Part 3: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WSAbtBJctN8

Part 4: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2572W0TInE

Link for Jim Pangburn:

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwGXZjIbrFU

Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=59RjWCvkGkw

Refferences:

- Jeannette Lasansky, “Slaves and Free African Americans in the Buffalo Valley, 1780-1850,” in African Americans in Union County: Slave and Free, 18.

- Bruce Teeple, “Post-Abolition Slavery in Pennsylvania (And How They Got Away With It),” in African Americans in Union County, 11, 13-15.

- Richard A. Sauer, “The Slavery Issue in Union County,” in Union County, Pennsylvania, and the Civil War, 14-33.

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, April 22). Copperhead (politics). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copperhead_(politics)

Leave a Reply